In a little more than four years from now, the twenty year extension given to existing copyrights by the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act will expire. Since copyright terms last through the end of the calendar year in which they first obtained copyright protection, 1 works will start going into the public domain as of January 1, 2019. As noted in a previous blog post, at the latest hearings before Congress on revisions to the Copyright Act, not one Representative and not one witness invited to testify put forth the proposition that copyright terms should be extended yet again. 2 So, it seems that the outer limit of constitutional copyright protection has been reached and there are no pending proposals from within Congress or in the entertainment industries to further extend copyright terms.

So Mickey Mouse, having first appeared in 1928 will scamper into the public domain on January 1, 2024, less than 10 years from now. But will he go quietly? I think everyone knows the answer to this. Certainly the entertainment conglomerate that is the Walt Disney Company will use very effort to assert continuing legal control over the world’s most famous mouse. But precisely how?

The answer lies in the realm of trademark law. Trademark law protects words, phrases and symbols used to identify the source of the products or services. Copyright protects works of artistic expression from being copied. So, on January 1, 2024, the very first Mickey Mouse cartoon Steamboat Willie will pass into the public domain, along with The Barn Dance. 3 The expiration of the copyrights in these films will mean that anyone can make copies of them. Many people also believe that this means that Mickey himself (Minnie and Pete as well) will also pass into the public domain, and anyone will be able to make new Mickey Mouse cartoons. This is by no means certain, as the application of trademark principles may prevent this.

The use of trademark law to protect works also subject to copyright is nothing new. The first 21 stories about Tarzan, being first published commencing in 1916, are now all in the public domain. 4 Yet, there are no rival stories about Tarzan being currently written by other authors. This is because heirs of Edgar Rice Burroughs, the creator of Tarzan, had the foresight to obtain a trademark on the name “Tarzan.” 5 Armed with this registration, they have been successful in preventing the distribution of works using the “Tarzan” trademark and variations. 6

Yet, does this not fly in the face of the constitutional requirement that copyrights only exist for a limited time? Does not giving trademark status to a character in the public domain in effect grant a perpetual copyright? It would seem that it does. The catch is that not all formerly copyrighted characters will qualify for trademark protection. In the one case that I could find that solidly addressed the issue, the Court ruled that in order for trademark to protect a character in the public domain, the character must have obtained “secondary meaning.” 7 In other words, one who encounters the character must immediately associate it with the source. In denying summary judgment to the Defendants, this Court held that “[d]ual protection under copyright and trademark laws is particularly appropriate for graphic representations of characters. A character deemed an artistic creation deserving copyright protection…may also serve to identify the creator, thus meriting protection under theories of trademark and unfair competition.” 8

Given an open invitation like that, Disney executives would be foolish not to run with it. And so they have. Disney has made Mickey Mouse so prominent in all of their corporate dealings, that he is effectively the pre-eminent symbol of the Walt Disney Company. There can be little doubt that anyone seeing the image of Mickey Mouse (or even his silhouette), immediately thinks of Disney. Leaving nothing to chance, Disney has also obtained 19 different trademark registrations for the words “Mickey Mouse,” including live action and animated television shows, 9 cartoon strips, 10 comic books, 11 theme parks, 12 and computer games. 13 Disney also has trademark registrations for Mickey’s visual appearance for animated and live action motion picture films. 14 This is where it gets very interesting. This is Mickey as he appears in Steamboat Willie:

This is Mickey as he appears today:

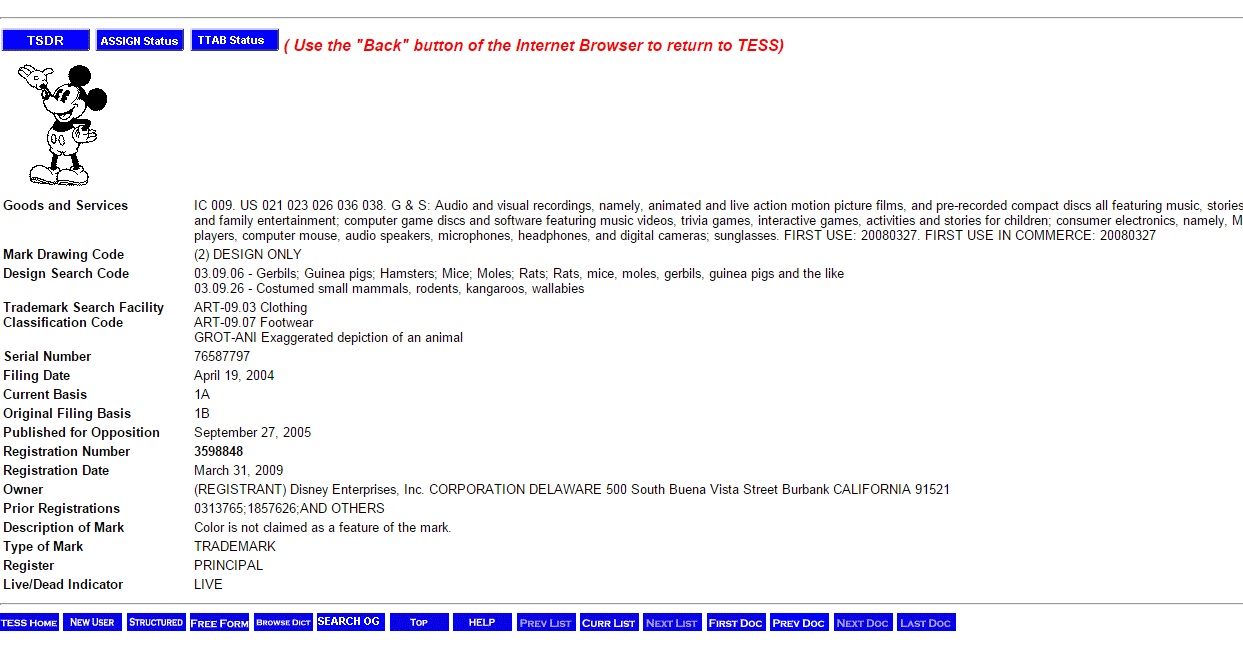

Quite a difference. Now here is the trademark registration for the visual aspects of Mickey as used in “animated and live action motion pictures:”

This really is more the Steamboat Willie Mickey, than the modern Mickey. Also note that the registration states that “[c]olor is not a claimed feature of the mark,” reinforcing that this registration is for the black and white version of Mickey, not the modern Mickey with his signature red shorts and yellow shoes. Also note the date the registration was filed: April 11, 2004. This would have been the year that Steamboat Willie would have entered the public domain, but for the passage of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act.

This really is more the Steamboat Willie Mickey, than the modern Mickey. Also note that the registration states that “[c]olor is not a claimed feature of the mark,” reinforcing that this registration is for the black and white version of Mickey, not the modern Mickey with his signature red shorts and yellow shoes. Also note the date the registration was filed: April 11, 2004. This would have been the year that Steamboat Willie would have entered the public domain, but for the passage of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act.

Much has been made of the allegation that the SBCTEA was really the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act.” 15 As noted previously in this blog, the most immediate beneficiary of the SBCTEA was Winnie the Pooh. The first Pooh stories were published in 1926, 16 and thus were set to go into the public domain in 2002. So, the first trademark versus public domain character dust-up will involve Pooh, not Mickey, and will present a very interesting test case.

Disney has indeed applied for and received trademark registrations for the “Winnie the Pooh” mark for a variety of products including “motion picture films.” 17 The problem that arises with Pooh, but not Mickey, is that Pooh did not originate with Walt Disney, but instead British author A.A. Milne. The visual depiction of the Pooh characters originates with artist Ernest H. Sheppard. 18 So, there is a large period of time for which Pooh was not associated with Walt Disney. Remember, the Court’s rationale for extending trademark protection to a copyrighted character lies in the assumption that “[a] character deemed an artistic creation deserving copyright protection…may also serve to identify the creator.” 19 The Disney company may own all the rights to the Pooh characters, but they are not the “creator” of Pooh, any more than they are the “creator” of Snow White. So, the only elements that Disney owns as a matter of being the “creator” are the elements they have added. For example, the Pooh of the books wears no clothing, but in all Disney versions he wears a red, short-sleeved turtleneck shirt.

No one would suggest that Disney could prevent a rival movie about Snow White, even though many people would associate Snow White with Disney. As recently as 2012, there was Snow White and the Huntsman made by Universal Studios. 20 So, it would seem that this result should apply to Pooh as well. Once the literary Winnie The Pooh enters the public domain, then anyone should be able to make copies of the book, the illustrations and produce new Winnie the Pooh material, including motion pictures based on the now public domain material.

Disney may file suit to prevent any competing Pooh movies or television shows on the basis of their trademarks and that Pooh has achieved secondary meaning, in other words, that a competing Pooh movie will be assumed to come from Disney by the general public. I think that assumption is not pre-ordained success. The Supreme Court of the United States has already cautioned “against misuse or over extension of trademark law and related protections into areas traditionally occupied by…copyright.” 21 Plus, it would seem that the producer of a new Pooh movie could survive the legal challenge by making it plain that the movie did not emanate from the Walt Disney Company.

Mickey is a different story. Not only did he originate with Walt Disney, but he has been presented as a corporate symbol for so long that the achievement of secondary meaning in the minds of the public is a foregone conclusion. Mickey is Disney, and vice versa. As troubled as I am by the prospect of Disney using trademark principles to effectively get eternal copyright protection for Mickey, I cannot fault the logic of the legal theory. However, I can speculate this will not lead to wholesale protection of copyrighted characters who enter the public domain as trademarks. This is because few characters will ever become famous enough to create a sufficient level of secondary meaning. “The Terminator” is certainly famous as a character, but do you remember what company made the movies? I could not tell you without looking it up. The same would apply to the “Alien” of that series of movies. James Bond is certainly world famous as a character, but his movies have been produced at three different Hollywood studios. It would be hard to say that Bond has achieved secondary meaning for any of them.

Of course, cartoon and comic book characters have an advantage in the secondary meaning analysis, because they have a stylized appearance that does not change significantly over time. Superman’s iconic costume is instantly recognizable and I think most of the public would recognize DC Comics as the source. Marvel Studios has been especially successful in associating its characters with the Marvel brand.

So in the end, the troubling aspect of effectively perpetual protection for a copyrighted character is balanced by the realization that Mickey Mouse is an outlier here. Few characters are so famous and so closely associated with their creators that this theory, if upheld by the Courts, would grant trademark protection to perhaps a handful of copyrighted properties.

Notes:

- 17 USC 305 ↩

- Copyrights Last Too Long! (Say the Pirates): They Don’t; And Why It’s Not Changing Anytime Soon ↩

- Mickey Mouse (film series) ↩

- Tarzan ↩

- The initial Tarzan registration is 0799908 was obtained in 1965 and is still a “live” trademark. ↩

- See Edgar Rice Burroughs, inc. v. Manns Theaters, 195 USPQ 159 Central District of California 1976. ↩

- Frederick Warne & Co. v. Book Sales Inc., 481 F.Supp 1191 at 1197 District Court for the Southern District of New York 1979. ↩

- Id. at 1197 ↩

- TM Reg. 3750188 ↩

- TM Reg. 0315056 ↩

- TM Reg. 1152389 ↩

- TM Reg. 3036883 ↩

- TM reg. 3006350 ↩

- TM Reg. 3598848 ↩

- The Disney Blog ↩

- 1926 – A.A. Milne Publishes Winnie-the-Pooh ↩

- TM Reg. 3038490 ↩

- 1926 – A.A. Milne Publishes Winnie-the-Pooh ↩

- Frederick Warne & Co. v. Book Sales Inc., at 1197 ↩

- IMDb – Snow White and the Huntsman ↩

- Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. 123 S.Ct 2041Supreme Court of the U.S. 2003 ↩