January 26, 2024 saw a jury return one of the most head-scratching copyright verdicts in recent memory. It ruled that a photograph and resulting tattoo of jazz icon Miles Davis, despite being hailed by the Defendant as being “identical,” were somehow not substantially similar to each other.

Under normal circumstances, I do not criticize jury verdicts. The jury hears all the evidence, not just what is reported in the press and online. Yet here, the visual evidence is so compelling, and freely available, that it has led copyright scholars to openly question the result. 1

The case arises from a photo of Miles David by photographer Jeff Sedlik, which was used, at the very least, as an “artist reference” by tattoo artist Katherne Von Drachenberg, professionally known as “Kat Von D.”

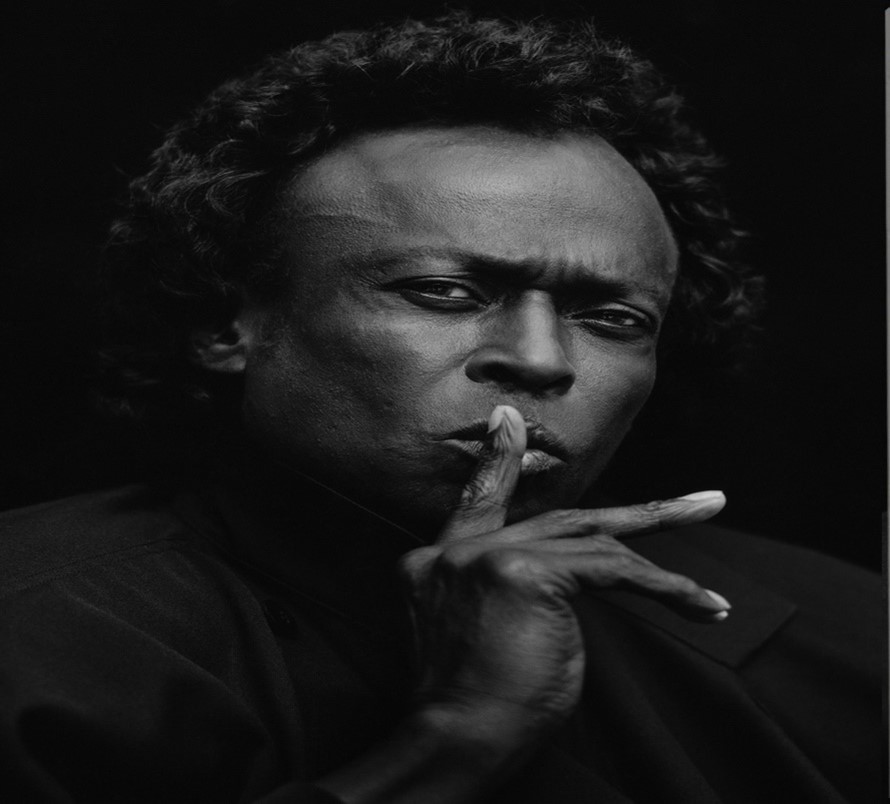

Here is the original photo by Sedlik:

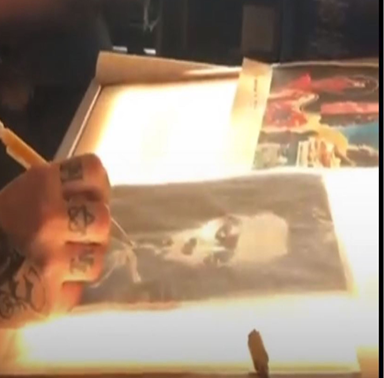

Here is a screengrab from a video showing Kat Von D tracing the photograph using a lightbox:

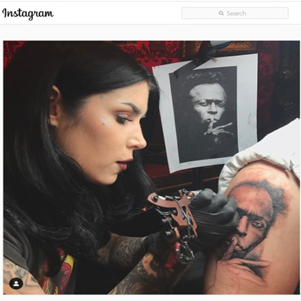

Here is a photo of Kat Von D inking the tattoo. Note the subject photograph is in the background.

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the photograph and finalized tattoo:

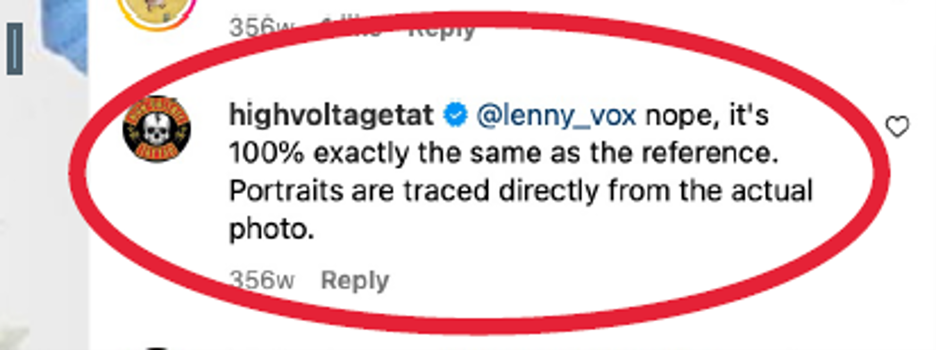

Here is an Instagram Post from High Voltage Tattoo (Kat Von D’s studio, since closed 2) stating that tattoos and references are identical:

Now, I ask you: are the two images not substantially similar? Especially where there is evidence of direct copying? Even further, should the question of substantial similarity even have been put before a jury? Existing 9th Circuit case seems to indicate that the answer is no.

“A finding that a Defendant copied a Plaintiff’s work, without the application of substantial similarity analysis, has been made only when the Defendant has engaged in virtual duplication of a Plaintiff’s entire work. (Citations omitted)… In those cases a substantial similarity analysis was unnecessary because the copying of the entire work was admitted. The infringement issue turned on whether the material constituted protected expression.” 3 (N.B. Some have suggested that this holding is in question after the 9th Circuit decision in Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, but having re-read that case, I don’t follow this reasoning.)

Nevertheless, the Court denied summary judgement and sent the question to the jury. This is the jury instruction on substantial similarity given by the Court:

“For the extrinsic test, you are to examine the similarities between what is protected by copyright law in the Miles Davis Photograph, on the one hand, with each of the accused infringements, on the other hand.

Photographs can be broken down into elements that reflect the various creative choices the photographer made in composing the image. These creative choices are elements such as the photograph’s subject matter, pose, lighting, camera angle, depth of field, and almost every other variant involved in the works.

The individual elements standing alone are not copyrightable. But if sufficiently original, the combination of subject matter, pose, camera angle, etc., receives protection as original expression. It is the plaintiff’s burden to identify the particular combination, selection, or arrangement of elements in his photograph that he claims is protected by copyright law. He must show that each of the accused infringements is substantially similar to this particular combination, selection, or arrangement.

If there is no substantial similarity at this first step, then the plaintiff has not met his burden.” 4

Whew. That’s a lot of explanation.

In any event, put more simply, if a tattoo is of Miles Davis, then the finished product needs to look something like Miles Davis, an element not subject to Sedlik’s copyright. The rest of it, particularly the “pose,” does seem to be the subject of Sedlik’s copyright, and moreover was copied exactly.

Just how confused was the jury? A lot it seems.

After finding down the line that Kat Von D’s work was not substantially similar to Sedlik’s photo, that should have ended the case. The jury form instructs the jury not to answer any remaining questions to which the answer was “no” on substantial similarity. Yet the jury plowed on.

It was given 10 examples of uses and whether they were fair use. Remember, having found no substantial similarity at all, it was not to answer any duplicate of these questions. Yet it found “fair use” on 4 out of the 10 cited uses.

Of particular note is that “Final Tattoo Social Media Posts” exhibits 209, 210 and 211, were all found to be not substantially similar, but the jury then ruled that these exact same uses (exhibits 209, 210 and 211) were “Fair Use.”

Let’s remember that fair use is an affirmative defense. In order to find that a certain use was fair use, it would have to have found that the use was otherwise copyright infringement. The jury’s verdict in essence contradicts itself.

So, what are the prospects on appeal?

Courts are all over the map on whether substantial similarity is a question of law or fact. Some say it’s even a mixed question of law and fact. But in any event, a question of law is reviewed by a Court of Appeals de novo, without any deference to the trial Court decision. A question of fact is reviewed for being “clearly erroneous,” if made by a Judge. This would apply to the denial of Selik’s summary judgement motion. Jury verdicts are harder to overturn. They are subject to a mere “reasonableness” standard. “The reasonableness standard of a jury verdict is generally for the verdict to stand unless no substantial evidence supports the decision.” 5

Having seen the evidence, (and now you have seen it too), I for one could very much see a reversal from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Notes:

- Jury finds Kat Von D tattoo does not infringe. But stand by. ↩

- Kat Von D sued for thousands as she shuts down famous tattoo parlor ↩

- Narell v. Freeman 872 F.2d 907 (9th Cir. 1989 ↩

- Jury instruction No. 20 ↩

- Identifying and Understanding Standards of Review ↩