On July 1, 2019, a Federal District Judge ruled that when Andy Warhol copied an unpublished photographic portrait of the late singer Prince, and created 16 different variations of the unpublished photo, that these were “fair use” and not copyright infringement. 1 Plaintiff, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, immediately praised the decision saying:

“Warhol is one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and we’re pleased that the court recognized his invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works.” 2

Upon reading that quote, my initial reaction was, this is totally beside the point. Why should the “fame” or “importance” of the artist factor into whether something is fair use or not? It turns out, maybe more than a little.

The facts of the case are fairly straightforward: 3

- Defendant Lynn Goldsmith took 11 photographs of Prince at her New York Studio in 1981

- Though the photos were created on assignment for Newsweek, the photos were never published

- Vanity Fair asked for and received a license from Goldsmith to use one of the Prince photographs “for use as an artist reference in connection with an article to be published…”

- Warhol created a single image which was used in connection with a 1984 article about Prince titled “Purple Fame” for which Vanity Fair gave Goldsmith a credit for the “source photograph”

- Sometime later, Warhol creates the “Prince Series” of 16 images based on the Goldsmith photograph, and begins to sell both originals and copies 4

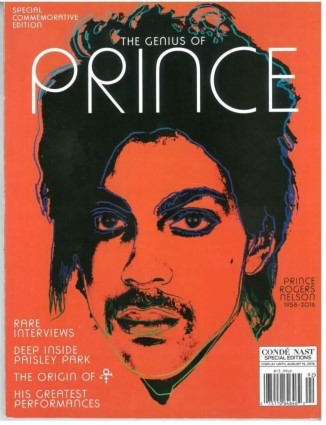

After Vanity Fair published one of the “Prince Series” in connection with a commemorative magazine after Prince’s death, Goldsmith contacted the Warhol Foundation stating that the use had infringed the copyright in her unpublished photographs. 5 Rather than wait for a lawsuit that might not come, the Warhol Foundation filed suit against Goldsmith, seeking a declaratory judgement of non-infringement, on the basis that the works are not substantially similar or alternatively “fair use.”

This pre-emptive strike against Goldsmith proved to be crucial in obtaining the favorable result. The Warhol Foundation filed suit in the Southern District of New York, the very cradle of the “transformative use” test, of which this blog has taken many opportunities to criticize. 6 Even further, SDNY is governed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, where the truly terrible (and criticized by other Circuits) decision in Cariou v. Prince remains good law, and binding precedent on the trial court. 7

While it is my normal policy not to reproduce the images that make up part of the dispute (as to not further the damage done), the extent to which the images have been altered forms such a crucial part of the Court’s ruling that I will reproduce them here.

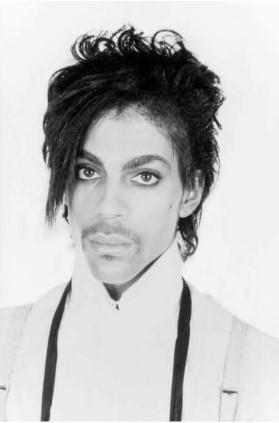

This is the Goldsmith photograph:

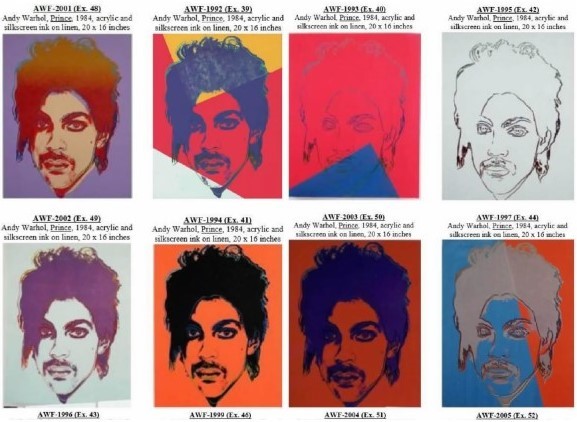

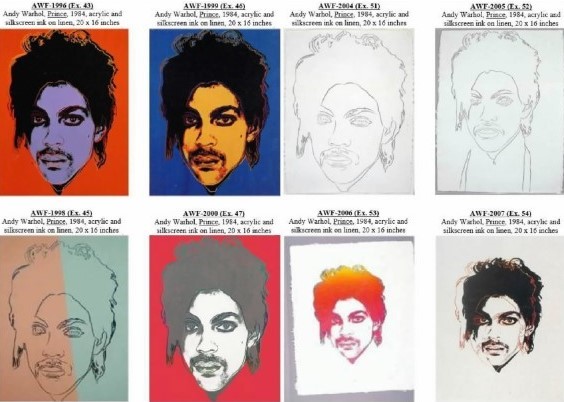

These are the Warhol variations that make up the Prince series:

Curiously, the Warhol Foundation refuses to admit copying of the photograph, but that “somehow” Warhol magically created the “Prince Series.” 8 Nevertheless, the Warhol Foundation does admit access and that there is sufficient “probative similarity” to establish that Warhol copied the Goldsmith photograph to some extent. 9

The Court never reaches the question of whether the works are substantially similar to each other. Instead, it focuses its efforts on the question of whether the “Prince Series” is in fact fair use.

Here is where the heavy hammer of Cariou and the “transformative use” test start to fall. If you accept Cariou as correctly decided, and this Judge must accept it as correctly decided, then a finding that Warhol’s edition are “transformative” is a foregone conclusion. Indeed, Cariou is cited to by the Court five times in a little more than a page at one point. In Cariou, sometimes there were only a few swatches of paint placed over the photographs.

Here, as the Court rhapsodizes:

“In all but one of the works, Prince’s torso is removed and his face and a small portion of his neckline are brought to the forefront. The details of Prince’s bone structure that appear crisply in the photograph, which Goldsmith sought to emphasize, are softened in several of the Prince Series works and outlined or shaded in the others. Prince appears as a flat, two-dimensional figure in Warhol’s works, rather than the detailed, three-dimensional being in Goldsmith’s photograph. Moreover, many of Warhol’s Prince Series works contain loud, unnatural colors, in stark contrast with the black-and-white original photograph. And Warhol’s few colorless works appear as rough sketches in which Prince’s expression is almost entirely lost from the original.” 10

In other words, they are derivative works under 17 USC 106(2), which are defined in section 101 as “… a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a… art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.” (emphasis added) So, in the circular logic of the “transformative use” test, any creation of a derivative work in which the work is “transformed,” and under the law should require a license, instantly becomes a “transformative use” and now “fair use,” which does not require a license.

Now, even though the Judge has already made a strong case that the changes made by Warhol are far more significant than those found to be transformative in the Cariou case, the Judge finds it necessary to add the following paragraph:

“These alterations result in an aesthetic and character different from the original. The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure. The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince – in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.” 11

This leads to the conclusion, as voiced by myself and others, that a lot of fair use, especially “transformative use,” turns judges to art critics, rather than triers of fact and deciders of law. Also, of what possible probative value to the case, is the fact that the “Prince Series” is “immediately recognizable as a Warhol?” Warhol had a very distinctive artistic style. A lot of artists do. He was also very famous as an artist, and therefore many of his works are famous. Should that matter?

Apparently it does.

“At the argument of the current motions, counsel for Goldsmith suggested that the fair use test is ‘almost like you know it when you see it.’ (citation omitted) This calls to mind Justice Stewart’s test for obscenity: ‘I know it when I see it.’ (citation omitted) If that were the test, it is plain that the Prince Series works are ‘Warhols,’ and the Goldsmith Prince Photograph is not a ‘Warhol.’” 12

“They add something new to the world of art and the public would be deprived of this contribution if the works could not be distributed. The first fair use factor accordingly weighs strongly in AWF’s favor.” 13

As to the second factor, the fact that the photographs were unpublished, and thus weigh against fair use, is given a curt two-sentence brush off:

“However, the reasons unpublished works enjoy additional protection against fair use – including respect for the author’s choices of when to make a work public and whether to withhold a work to shore up demand– carry little force in this case, where Goldsmith’s photography agency licensed the photograph for use as an artist’s reference. Moreover, this factor is of limited importance because the Prince Series works are transformative works. Therefore, the second fair use factor favors neither party.” 14

This analysis seems to be at odds with the Supreme Court’s holding in Harper and Row v. Nation Enterprises. 15 There, the Court stated:

“We conclude that the unpublished nature of a work is “[a] key, though not necessarily determinative, factor.” 16

Here, the mere fact that the work is “transformative” in the eyes of the Court trumps the fact that the work is unpublished and is a “key factor.”

It is at the third factor that the Court really misses the mark.

“All but one of Warhol’s works include only Prince’s head and a small portion of his neckline; Goldsmith’s photograph captures much of Prince’s torso. The sharp contours of Prince’s face that Goldsmith emphasized in her photograph are softened in some Prince Series works and traced over or shaded in others. Moreover, the three-dimensional effect in the photograph, produced by the background and lighting that Goldsmith chose, was removed by Warhol resulting in a flat, two-dimensional and mask-like figure of Prince’s head. And in the majority of his Prince Series works, Warhol traded Goldsmith’s white background for a loudly colored background. Indeed, unlike Goldsmith’s photograph, most of Warhol’s works are entirely in color, and the works that are black and white are especially crude and the creative features of the Goldsmith Prince Photograph are especially absent. Ultimately, Warhol’s alterations wash away the vulnerability and humanity Prince expresses in Goldsmith’s photograph and Warhol instead presents Prince as a larger-than-life icon.” 17

This ignores the Supreme Court’s holding in Harper and Row v. Nation Enterprises.

“As the statutory language indicates, a taking may not be excused merely because it is insubstantial with respect to the infringing work. As Judge Learned Hand cogently remarked, ‘no plagiarist can excuse the wrong by showing how much of his work he did not pirate.’ (citation omitted) Conversely, the fact that a substantial portion of the infringing work was copied verbatim is evidence of the qualitative value of the copied material, both to the originator and to the plagiarist who seeks to profit from marketing someone else’s copyrighted expression.” 18

As with Harper and Row, Warhol took the “heart of the work,” indeed the only part that really mattered: Prince’s face. Ask yourself: “What value would Warhol’s works have if they did not feature Prince’s face?” None, of course. Would you buy a Warhol that consisted on only the clothes Prince was wearing that day, with his face blotted out or concealed? Of course not.

Prince’s face, as captured by Goldsmith, is the “heart of the work,” and factor three should have weighed heavily in her favor.

As to the fourth factor, the court concludes:

“Goldsmith’s evidence and arguments do not show that the Prince Series works are market substitutes for her photograph. She provides no reason to conclude that potential licensees will view Warhol’s Prince Series, consisting of stylized works manifesting a uniquely Warhol aesthetic, as a substitute for her intimate and realistic photograph of Prince. Although Goldsmith points out that her photographs and Warhol’s works have both appeared in magazines and on album covers, this does not suggest that a magazine or record company would license a transformative Warhol work in lieu of a realistic Goldsmith photograph.” 19

Judge, this is an assumption that has been disproved by actual events. And the proof is contained in your own opinion:

So in sum, is the Warhol case correctly decided? Yes. Absolutely. The Judge is bound to follow Cariou, which had much less “transformation” than is present here.

Is the decision terrible? Yes. Consider the following.

Remember, Goldsmith, the photographer whose work was copied, is the Defendant here. The Andy Warhol Foundation sued her, to boldly establish their right to freely plagiarize her work. The end result is she spent $400,000 defending herself. In order to appeal, it might cost her $2.5 million before it is all done. 20 She has started a GoFundMe Page to help pay her legal fees. 21

Sort of puts the Warhol Foundation’s proclamation that “we’re pleased that the court recognized his invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works” in a whole new light, doesn’t it?

Or consider this. These kinds of decisions pave the way for bootleg knocks-offs of famous artists’ work. 22 Like Eric Doeringer, the subject of a New York Times profile.

“In the art world, auction prices are pretty much the only public record of what a work is worth, so it sort of sets the value of artists’ work,” Mr. Doeringer said. “The idea was to take this event and knock it off and make these multimillion dollar works of art available for a lot less.”

On the studio walls hung Mr. Doeringer’s versions of works by Frank Stella, Wayne Thiebaud, Kaws, Giorgio Morandi, Rauschenberg and Warhol. The knockoffs are smaller than the pieces they’re based on and with clear imperfections — a wobbly line here, a visibly pasted-on bit there — but instantly recognizable.

“They’ll fool you from a distance,” Mr. Doeringer said. “They won’t fool you close up.” 23

So copy a work, make some changes, and presto! Transformative use!

Maybe the remedy for Ms. Goldsmith is to take the “Prince Series” and make her own “transformative use” of them. Take the 16 images and chop them up into small bits. Make a mosaic. Make some bits larger than others. Paste some of them upside down. Add a few Jackson Pollock like scribbles on top.

And presto! According to the reasoning of this Court – instant “transformative use”!

Not that she should do this.

But she could.

Notes:

- Andy Warhol foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith 2019 WL 2723521 all references are to the WestLaw pagination ↩

- Warhol’s Prince Image Doesn’t Violate Copyright, Judge Rules ↩

- Warhol v. Goldsmith at 2-3 ↩

- Id. at 3-4 ↩

- Id. at 4 ↩

- Marching Bravely Into the Quagmire: The Complete Mess that the “Transformative” Test Has Made of Fair Use ↩

- Warhol at endnote 7 ↩

- Id. at 3 ↩

- Id. at 5 ↩

- Id. at 7 ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at endnote 8 ↩

- Id. at 7 ↩

- Id. at 8 ↩

- 471 U.S. 539 Supreme Court of the United States 1985 ↩

- Id. at 554 ↩

- Warhol at 9 ↩

- 471 U.S. at 565 ↩

- Warhol at 10 ↩

- Warhol’s Prince Image Doesn’t Violate Copyright, Judge Rules ↩

- Warhol Foundation vs Goldsmith GoFundMe ↩

- Move Over, Richard Prince. Here Comes Bootleg Art From ‘Christy’s.’ ↩

- Id. ↩