On August 19, 2015, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals weighed in on a topic that has bedeviled courts for years: what parts of an article of clothing are copyrightable?

Fashion designs are generally not eligible for copyright protection because they are “useful articles.” 1 Even when the designer adds more decorative elements, this is usually not enough to move a dress into a work of art. 2

“[T]he creative arrangement of sequins, beads, ribbon, and tulle, which form the bust, waistband of a dress, do not qualify for copyright protection because each of these elements (bust, waistband, and skirt) all serve to clothe the body.” 3

This is why you see a dress in Sak’s Fifth Avenue one week and a few weeks later you see the same dress in Target.

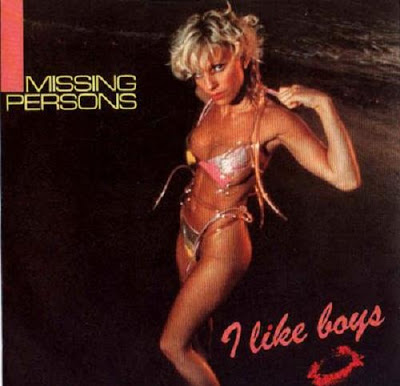

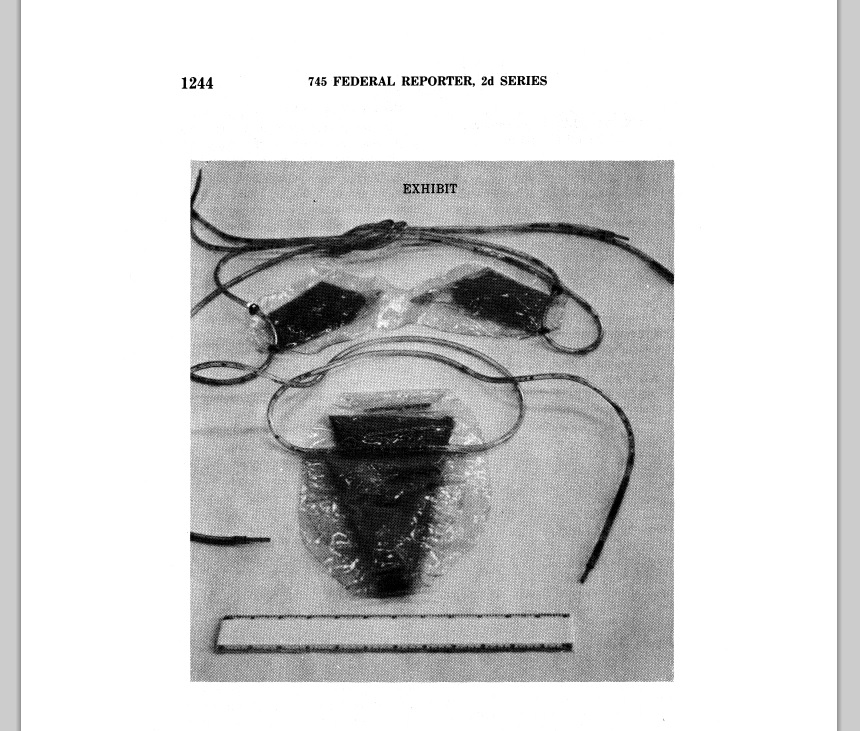

This has led to some fairly elaborate theories to take a work of clothing out of the realm of “useful article.” In the case of Poe v. Missing Persons, the creator of an off-beat woman’s bikini was successful in obtaining a reversal of a summary judgement. He argued that what he had created was a “soft-sculpture” and not a just an outlandish bikini and thus became a disputed issue of material fact which precluded summary judgment. 4 Below is a photograph that was placed into evidence of the “soft sculpture” and for comparison’s sake, a photograph of the lead singer of the band “Missing Persons,”, wearing the “soft sculpture.” You can decide for yourself whether this argument is convincing or whether the 9th Circuit has gone off the rails again.

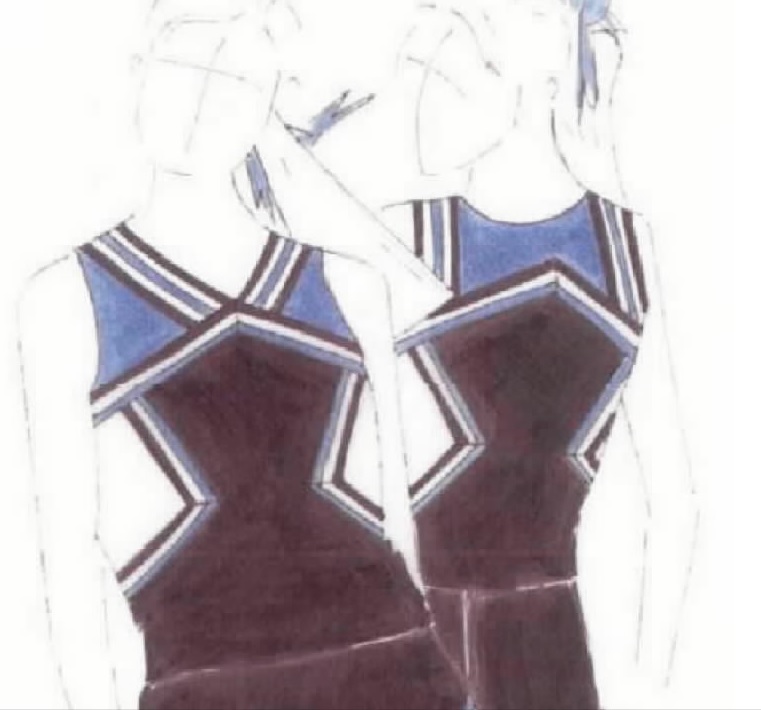

This argument was unavailable for the Plaintiffs here, Varsity Brands, Inc. They are unquestionably a company that manufactures and sell uniforms for cheerleaders. Their complaint was that a competitor, Star Athletica, LLC, had copied some of their designs. 5

Crucial to an understanding of the case is the visual aspect of the designs which were registered by Varsity Brands with the Copyright Office.

The Defendant argued successfully at the District Court level that despite the Copyright Office granting registrations for the design, the designs were merged into the “functional purpose ” of a cheerleader uniform and thus not eligible for copyright protection. 6

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, in a 2-1 decision, disagreed with both these points.

“[A]gency interpretations of a statute deserve “respect proportional to [the interpretations’] ‘power to persuade,’ … when the agency has ‘specialized experience and broader investigations and information available’ than those available to the judiciary… We now hold that the Copyright Office’s determination that a design is protectable under the Copyright Act is entitled to [greater] deference. Individual decisions about the copyrightability of works are not like “rules carrying the force of law,” which command [lessened] deference.” 7

The Court went on to recognize that while fashion designs have generally held not to be copyrightable, that the same is not true for fabric designs.

“[I]t is well-established that fabric designs are eligible for copyright protection. (citation omitted) We therefore conclude that a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work’s ‘decorative function’ does not render it unable to “be identified separately from,” or “[in]capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” 8

In other words, the designs created by Varsity Brands are copyrightable to the extent that they can be separated either physically or conceptually from the useful article and are capable of existing independently. The Court goes on to conclude that Varsity Brands designs meet this test.

“All of Varsity’s graphic designs are interchangeable. Varsity’s customers choose among the designs in the catalog, including the five designs at issue, select one of the designs, and then customize the color scheme. (citation omitted) The interchangeability of Varsity’s designs is evidence that customers can identify differences between the graphic features of each design, and thus a graphic design and a blank cheerleading uniform can appear “side by side”—one as a graphic design, and one as a cheerleading uniform. (citation omitted) We therefore conclude that each of these graphic design concepts can be identified separately from the utilitarian aspects of the cheerleading uniform.” 9

“Varsity’s designs ‘may be incorporated onto the surface of a number of different types of garments, including cheerleading uniforms, practice wear, t-shirts, warm-ups, and jackets, among other things.’ (citation omitted). This evidence establishes that the designs are transferrable to articles other than the traditional cheerleading uniform (citation omitted). In addition, the interchangeability of Varsity’s various designs is evidence that the graphic design on the surface of the uniform does not affect whether the uniform still functions as a cheerleading uniform. Indeed, ‘nothing (save perhaps good taste) prevents’ Varsity from printing or painting its designs, framing them, and hanging the resulting prints on the wall as art. (citation omitted) We therefore conclude the arrangement of stripes, chevrons, color blocks, and zigzags are ‘wholly unnecessary to the performance of’ the garment’s ability to cover the body, permit free movement, and wick moisture.” 10

Yet, let us not forget the doctrine of independent creation. While the designs created by Varsity Brands are certainly bold and colorful, they are not particularly striking as an original work of art. While the majority is correct that these designs, if transferred to a canvas, would qualify for copyright protection, the use of colorful stripes, parallel lines and chevrons is so ubiquitous in cheerleader uniforms that in order to successfully sue for copyright infringement there would have to be a very high level of proof of access and copying. This is especially true where there are most likely numerous manufacturers of cheerleader uniforms, all using the similar designs utilizing stripes, parallel lines and chevrons.

The dissent makes the following points:

“[T]he particular athletic uniforms before us serve to identify the wearer as a cheerleader. Without stripes, braids, and chevrons, we are left with a blank white pleated skirt and crop top. As the district court recognized, the reasonable observer would not associate this blank outfit with cheerleading. This may be appropriate attire for a match at the All England Lawn Tennis Club, but not for a member of a cheerleading squad.” 11

“It is apparent that either Congress or the Supreme Court (or both) must clarify copyright law with respect to garment design. The law in this area is a mess—and it has been for a long time. (citation omitted) The majority takes a stab at sorting it out, and so do I. But until we get much needed clarification, courts will continue to struggle and the business world will continue to be handicapped by the uncertainty of the law.” 12

True, but this issue is but one of many murky issues in the realm of copyright law, particularly “transformative use.” 13

In the meantime, when Varsity Brands yells out “Gimme a ©!” the Courts and the Copyright Office will say “You’ve got it.”

Notes:

- Knitwaves, Inc. v. Lollytogs Ltd., 71 F.3d 996, 1002 (2d Cir.1995); Folio Impressions, Inc. v. Byer Cal., 937 F.2d 759, 763 (2d Cir.1991) ↩

- Jovani Fashion, Inc. v. Fiesta Fashions, 500 F. App’x 42, 44 (2d Cir.2012) ↩

- Jovani Fashion, Inc. v. Cinderella Divine, Inc., 808 F.Supp.2d 542 (S.D.N.Y.2011) at 550 ↩

- Poe V. Missing Persons, 745 F.2d Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal (1984) ↩

- Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica LLC, Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals 2015 WL 4934282 ↩

- Id. at page 7 ↩

- Id. at pages 8-9 ↩

- Id. at 16 ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. at 19 ↩

- Id. at 20 ↩

- Marching Bravely Into the Quagmire: The Complete Mess that the “Transformative” Test Has Made of Fair Use ↩